The First Paper Money and Stock Market Bubble: Is John Law the Father of QE?

Great Scot! How a murderer became richer than the king of France

“There must be something in the soil that produces such men, something in the land of the mountain and the flood that compels exertion…”

— Andrew Carnegie on the Scottish, A Biography of James Watt, 1957

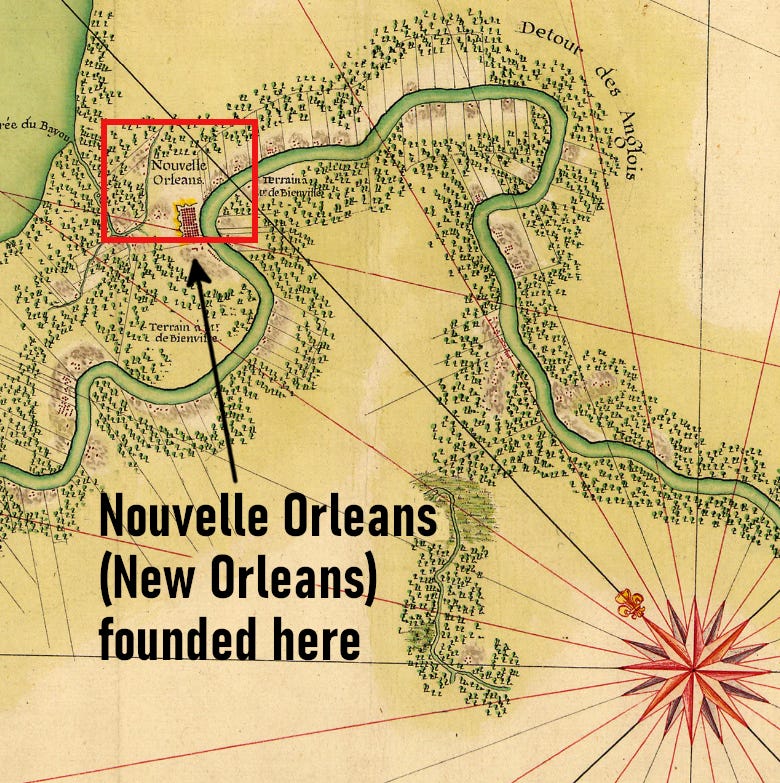

309 years ago, John Law strode into the Parisian palace of King Louis XV and declared that a golden wonderland existed on the far side of the Atlantic, where the hills were littered with gold and precious gems, ripe for the picking.

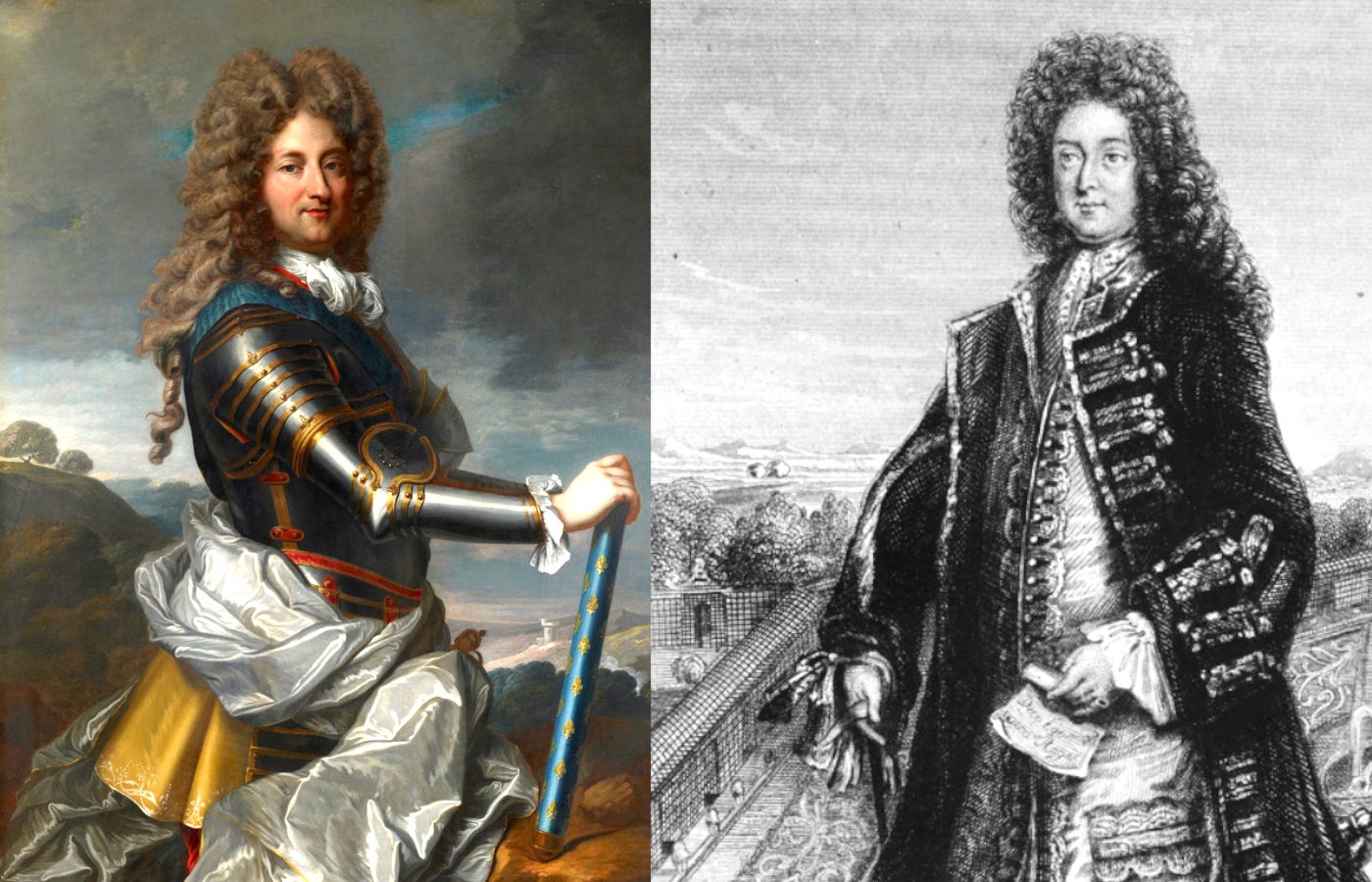

The foppish 44-year-old Scotsman was not addressing the boy-king himself — who was only six, and still playing with wooden toys — but the man who ruled the French realm in his place: the Regent, Duke Philippe II of Orleans.

Fortunately for Law, Philippe was desperate.

He was an excellent soldier and general, having won important victories in Belgium in the 1690s and in the following decade in the War of Spanish Succession, but his talents did not extend to money management, nor to self-control.

His public reputation as a womaniser, drunkard and gambler was so wretched that he was suspected of poisoning four of his family members in his quest for absolute power.

“Living perpetually in the company of loose women…he was habituated to debauchery to the point of being unable to do without it, and was rumoured only able to amuse himself with rowdy orgies.”

— Alfred Cobban, A History of Modern France, 1964

The French national finances were in a perilous state, ravaged by the years of war waged by Louis XIV, and the king’s credit overextended to the point where Philippe seriously considered declaring the Crown bankrupt.

Unfortunately for the duke, the picture Law had painted was total and utter bullshit.

The Mississippi Delta in 1715 was, not in fact, a shimmering Eldorado, but a mosquito-infested swamp, its largest town populated by a handful of slaves, convicts and prostitutes. While the area had been used as trading stage by Native Americans, there was no mineral wealth.

The main export from this brackish and subtropical quagmire was blue indigo dye, a humble parcel so pitifully low in weight-to-value ratio that aghast French sea captains refused to load it when they sailed into the Louisiana1 port in John Law’s promised land.

Still, within five years the Scotsman would manage to seize control of – then ruin – the economic affairs of France.

His Mississippi Bubble was certainly the first monetary inflation (and stock market crash) of the modern era.

Described variously as a gambling addict, a “financial scoundrel”2 and one of the greatest economists of the last 400 years, the tale of John Law is almost as insane as the results it produced.

He had first made the acquaintance of Philippe of Orleans in the gaming dens of Paris, where it was said he would approach the roulette wheel3 with a gigantic bag of gold coins in each hand.

It is worth noting that he failed to mention to the soon-to-be Regent that he had escaped from prison after murdering London’s most celebrated socialite4 two decades earlier, and was still on the run.

But by his 20s this extraordinary man had developed an irrepressible taste for risk-taking; a talent for spinning fantastical yarns; and an absurdly heretical policy for issuing paper (!) money in place of gold.

Before we go back, let’s go forward

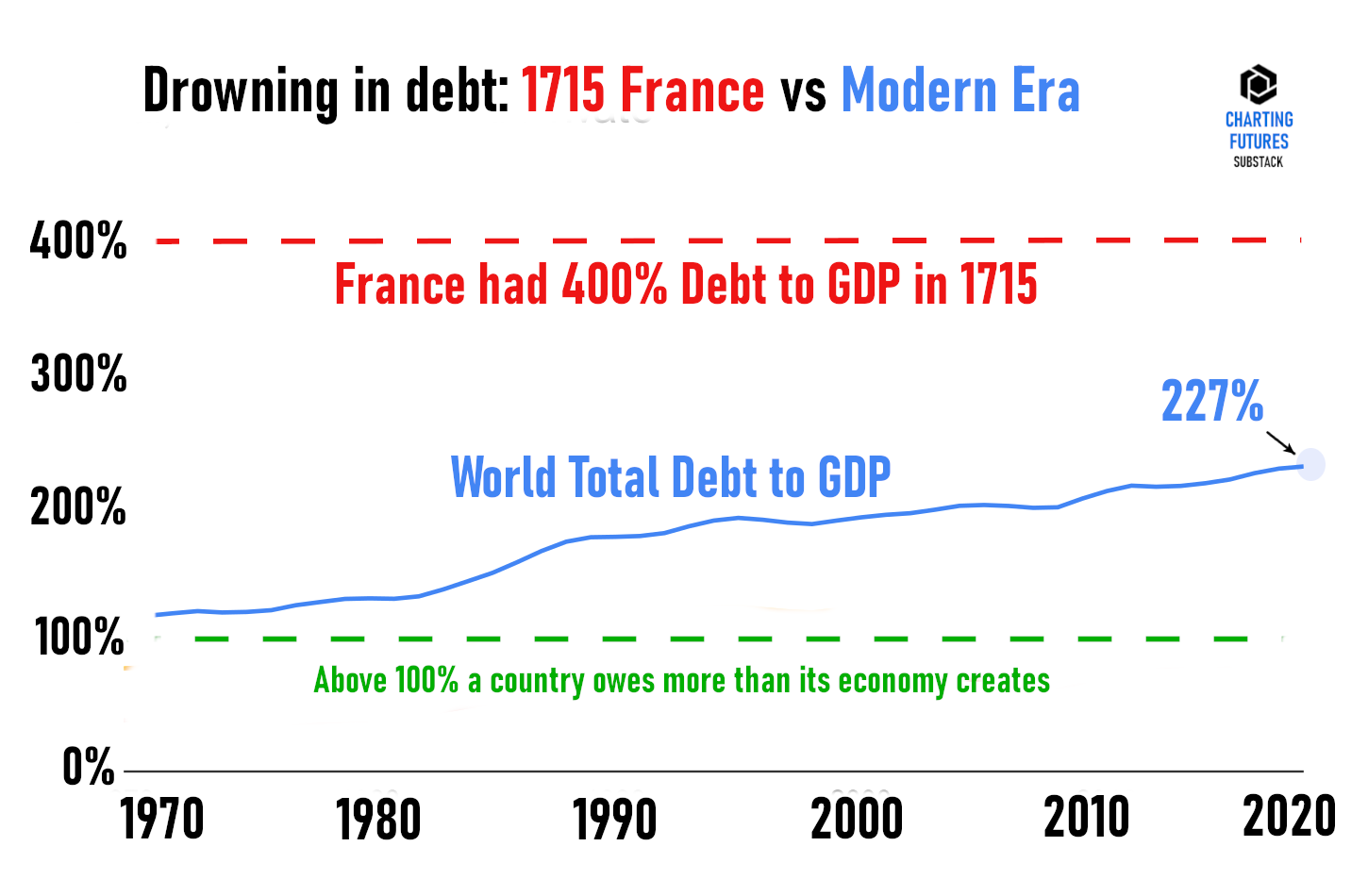

Some estimates suggest France’s debt-to-GDP ratio at the time of Philippe’s Regency was as high as 400%. That deficit is more unbalanced than during the French Revolution in 1789, a state of affairs that killed off absolute monarchy under Louis XVI.

GDP is the Gross Domestic Product of a nation: a stock measure of the total value or output it creates yearly. While in the below chart, we can see that the world’s total debt is far higher than its output, economists tend to say that this level is manageable. It’s all a question of perspective, I suppose.

For nations with low international standing and a poor history of paying back what they owe, when they find themselves in a position where debt is dramatically higher than GDP, things start to break.

For one, creditors, or the people who have loaned you money, start to ask for far higher interest payments to be compensated for the risk that you will go bankrupt and they will not get paid back at all.

When debt to GDP rises above 100%, as it has for most developed nations in our modern era, a state owes more in debt that it produces.

Because of the fact that every country now owes every other country far more than they will ever be willing to pay back, it seems like the only way out is via a series of debt forgiveness programs — or debt jubilees5.

We are starting to see the first of these come into action, an extremely sensible decision in my view, as President Joe Biden is doing with student debt in the US right now. Both US and UK student debt is largely government owned, and so deleting the balance owed is relatively simple.

It gets more difficult to forgive debts when they — and the mountains of money in interest they pay over decades — are owned by banks, money managers and public companies. If we forgave all those debts — the value of UK pensions would almost certainly crash.

The largest British workplace pension provider NEST, for example, has 15% of its £36bn in holdings in illiquid assets that are difficult to quickly turn into cash, including private and corporate debt, and said in February 2024 it wanted to double that allocation to 30%.

Anyway, back to France

Those who were aiming to overthrow the system in 1715, more than 70 years before the French Revolution that toppled the 1,000-year reign of kings, had little knowledge of the true crisis in the royal finances.

French nobles and the royal houses fumed as they saw their bitter rivals, the drastically smaller nations of England and Holland, build up lavish monopolies in fishing, tobacco and all manner of prized goods from their various colonies in the Caribbean, India and the wealthy east coast of what would become America.

Credit had been these two nation’s real gateways to wealth. How else could they have supported national debts at a level that was crushing France?

John Law calculated the French Crown in 1715 was paying 165 million livres a year (8% interest) on its debts of 2 billion livres. This was more than the state was bringing in from its entire annual tax revenue. France was, to all intents and purposes, already bankrupt.

Bringing that interest rate down to a more manageable 2% would free up an enormous amount of capital. But how to do it? How would you make a nation seem much more creditworthy with the flick of a quill?

A Wealth Tax seemed the most obvious way out. It is something more people are calling for today in the UK, at the very least.

But the French state had tried this reform, and it had failed. Before Louis XIV died, his comptroller-general had put forward a radical plan to make noble landowners and religious clergy pay taxes, alongside the rest of the nation.

Predictably, Philippe’s courtiers and advisors sneakily sold tax immunity to those wealthy financiers who could afford it.

“Capital will go where it is wanted and stay where it is well treated. It will flee from manipulation or onerous regulation, and no power can restrain it for long.”

—Walter Bigelow Wriston, The Twilight of Sovereignty, 1993

While some bankers and loan-givers who could not buy their financial freedom were condemned to row French ships in the galleys, many committed suicide, and the plan was quietly shelved when protests began in earnest.

Law’s realisation on money

In Amsterdam, where he had studied the operations of the Wisselbank, the world’s first central bank, Law had come to the conclusion that money was not the actual measure of a nation’s wealth, and its best use was not for its intrinsic worth, but as a means of exchange for increasing trade.

Real national wealth depended on the size of a population, its material resources, and the ability to move those resources around the world. That trade depended on money supply.

And so his main idea was that the mass shortage of available currency was the real handicap to the French economy. The radical solution he wanted to try was to create a royally-backed bank of paper money, instead of using gold, with the paper money guaranteed by the king’s credit.

Kings — especially those that believe they have a divine right to do what they want — had a terrible record with money.

And wherever there is debt, there are sovereign debt defaults. One of England’s first royal defaulters was King Edward III, a popular monarch but an inveterate fan of hugely expensive wars.

In 1337, he failed to pay back 1.5 million florins of loans to the Italian banking families of Peruzzi and Bardi, leading to their collapse. King Edward III may have been paying loan-shark levels of annual interest — up to 40% — on these debts.

(Legend has it that a descendent of the Peruzzi family turned up in England in 1830 with a bill for the Mayor of London John Crowder, with an estimation of the additional interest owed over the preceding 493 years.)

So what the Dutch and later English central banks actually did was to provide their traders with abstractions of money — in much the same way that, several hundred years later, Bitcoin would turn money into an abstraction — tokens — that could be traded around the world and instantly settled (made final) using the internet.

Instead of having to carry around heavy lumps of gold in a ship’s hold that could easily be plundered by pirates, each Dutch trader had an account with the Bank of Amsterdam. And the true innovation was introducing a book-entry ledger system, which allowed traders to settle payments with anyone else who also had an account with the Bank.

These money abstractions6 greased the wheels of trade, and made it much faster and easier for merchants to buy and sell things:

Without having to have the exact amount of precious metal in their hands before they could take delivery of furs, bales of tobacco, or whatever exotic foreign goods they had found in the colonies

Without having to figure out on the spot the correct exchange rate between two different coins or currencies (if 1 florin equalled 1 lira, or 0.2, or five, or 10)

Knowing that the bank at home in Amsterdam kept their gold or coins safe in a vault and their value was guaranteed by the state.

From the founding of the bank in 1609, until the mid-1800s, the Dutch guilder became what we call the global “reference currency” — the one type of money that all internationally-traded goods are priced in. You will see the same today with the US dollar: everything from oil to Bitcoin is priced in dollars as standard.

The Law of Unintended Consequences

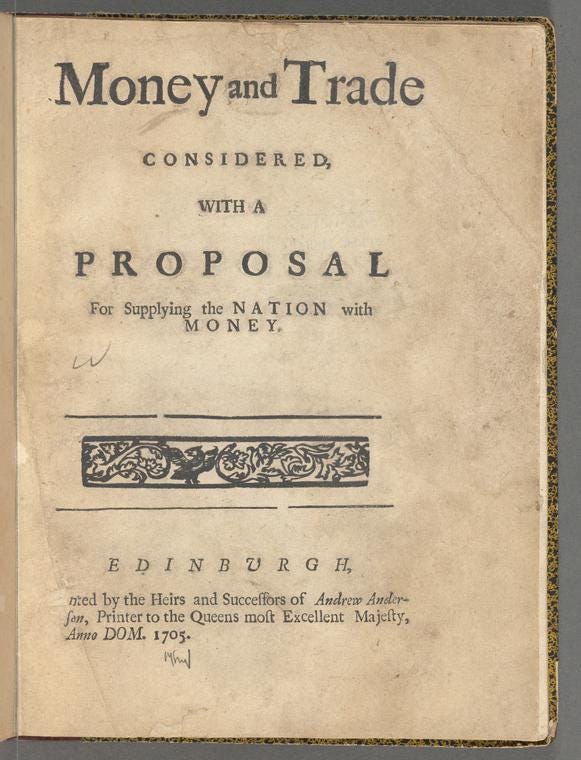

In 1705 John Law published his most famous book: Money and Trade Considered: with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money.

Still wanted for the killing of a man on Bloomsbury Heath, he was forced to publish anonymously. One can only imagine how galling it would be for an egotist and self-promoter like Law to have his name scrubbed from the title page.

Law immediately took his proposal to the Scottish Parliament, advising his native government to bypass its money shortage and economic woes by the radical idea of issuing paper currency, backed by the value of Scottish land.

These are the ideas he would later put into practice in France.

Again: he suggested that the true value of money, which ran in direct opposition to Scottish economic thought at the time, was not in its individual worth. Instead, it was from that money’s ability to stimulate trade between other countries, and deal in the buying and selling of goods thousands of miles away.

He argued passionately that reducing money to a means of exchange would produce self-sustaining cycles of consumption, and spending, and job-creation, and productivity, elevating Scottish wealth with the riches of the New World.

Clearly, the economics of the state would have been dire when Law presented his treatise to the Scottish parliament in 1705. And it was financial necessity which drove the Scots towards the seismic shift of a political union with England just two years later, in 1707.

There are two possible reasons why he never returned home.

First: seeing his idea rejected; and second: seeing that the men who laughed him out of Parliament House in Edinburgh were just two years later forced into a marriage of convenience with the hated English. It was too much to bear.

Instead he took his plans and lofty ideals to the Continent.

Within 12 months of meeting Phillipe of Orleans, and beating him in various games of skill and chance, John Law shocked the political world by winning the right from the Regent to open a French national bank.

One secretary at the British embassy wrote at the time that: “Law’s bank has ruined all the banquiers here.”

It would be for good reason that it took another six decades before France allowed the creation of another public note-issuing bank.

With the benefit of 300 years of hindsight, the result of a sudden expansion of economic growth using printed money seems obvious.

In our era, there is a famous meme of the US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell soberly enacting the solemn monetary policy tool of Quantitative Easing by furiously pumping the money printer. And they say kids have no sense of humour.

A little history goes a long way

So where did this heretic come from, exactly?

What we know is true is that John Law was the son of an Edinburgh goldsmith and banker, born in the Scottish capital 353 years ago this week, on 21 April 1671.

He went into his father William’s business at the age of 14 in 1683, but showed little interest, and preferred to use his talent for counting cards and calculating odds on games and gambling (especially on tennis).

That year, William had bought Lauriston Castle, a sumptuous manor house with 30 acres of grounds northwest of Edinburgh, overlooking the spectacular Firth of Forth.

In this same house, 100 years earlier, the astronomer John Napier had invented the logarithm7: a mathematical tool for the much simpler calculation of very large numbers.

No-one in the Law family got to enjoy their raised status, as William died just weeks after laying down the cash to buy the grand estate.

And John had racked up such enormous debts as a teenager that his mother threw him out of their city-centre townhouse, noting his obsession with staying up until dawn to play “the Lotterie and other games”. In 1693 he was forced to sell her his stake in the Lauriston estate so she could pay off his enraged creditors.

Just 12 months later, he would be convicted of murder.

When we continue, we find out how Law’s System emerged, the incredible reaction of the French, and how exactly the insane Mississippi Bubble story unfolds.

The French explorer La Salle claimed the land West of the Mississippi River for France in 1682, naming the region Louisiana in honour of King Louis XIV.

JK Galbraith, A History of Economics: Past as Present, 1987

The French mathematician and physicist Blaise Pascal (actually a tax collector by trade) invented the earliest version of a roulette wheel in 1665, while he was attempting to devise a perpetual motion machine.

Edward “Beau” Wilson was a handsome army captain of questionable Norfolk stock, whose family circumstances were much reduced from their height. Appearing as if from nowhere with fabulous and conspicuous wealth, within a short few months he became the most famous dandy in London. Some gay history sources suggest this lavish money-spending was due to the fact that he was the noted lover and ‘kept-man’ of Charles Spencer, the 3rd Earl of Sunderland (whose direct descendants included Princess Diana).

Deuteronomy and Exodus both contain passages describing debt forgiveness, and one of the earliest records of the cancellation of public debts came in 594 BCE from the Greek lawmaker Solon, described by Aristotle as “the first people’s champion”.

Dutch trade coins, including liondollars and silver ducats, became staple currency both in the Netherlands and the rest of Europe until the end of the 18th century.

Napier invented ‘powers’ of numbers with a consistent base: for example, three to the power of two (3x3) equals 9, while three to the power of eight (3x3x3x3x3x3x3x3) equals 6,561. Astronomically large numbers could be written out and calculated much more easily, using this abstraction. Napier’s tables were still in use in schools up to the 1970s, when (thank god) electronic calculators took over.